“Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story” Offers an Intimate Portrait

Corky Lee, by his own account, took over 800,000 pictures of the AAPI community in his lifetime. His photographic output comprises an extensive archive, capturing the AAPI experience across the US. Despite his travels, however, Lee is likely best known for his steadfast and close documentation of Manhattan’s Chinatown. The vast majority of his oeuvre is remarkable for both its tight spatial circumscription and temporal span: the few square blocks of Manhattan’s Chinatown from the inception of the Asian American movement up until its recent pandemic-era resurgence, roughly two square miles over half of a century. Filmmaker Jennifer Takaki met the legendary photographer two decades ago and began following him with the initial plan of producing a five-minute vignette. The long-awaited, feature-length culmination of those efforts, Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story, will have its theatrical premiere at DCTV’s Firehouse Cinema on April 19.

Photographic Justice attempts to piece together a personal history that has become so indelibly tied to shaping the representations of a collective one. Born and raised in Queens to Chinese immigrants who ran a laundromat, in many ways Lee’s childhood is a prototypical Asian American story. After graduating with a degree in American History, he got his start as a community organizer, photographing building code violations in the Two Bridges neighborhood and helping tenants advocate for improved living conditions. In 1975, Lee’s photo of the protests incited by the police beating of Peter Yew ran on the front page of the NY Post. It was a pivotal moment for Lee and Chinatown at large, in which both, counter to the prevailing narrative surrounding AAPI at the time, established themselves to the outside world as inimitable political forces.

Some of Lee’s most recognizable photos are similarly profound records of devastation and of communities, justifiably, in uproar. There is the haunting gaze of a grieving Lily Chin, mother of Vincent Chin, who was murdered days before his wedding by two disgruntled autoworkers in Detroit (1982). Or members of Sikh community shrouded in stars and stripes, preemptively demonstrating their national loyalties in the wake of 9/11 (2001).

Yet in between explications of such career-defining images, we see that the vast majority of Lee’s work veers toward the celebratory. He rattles off the annual calendar of local AAPI festivals and parades by month; interviews with friends and community members repeatedly reference his perennial presence at such events. Lee lightheartedly recounts witnessing and capturing the first Asian American woman to win Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest.

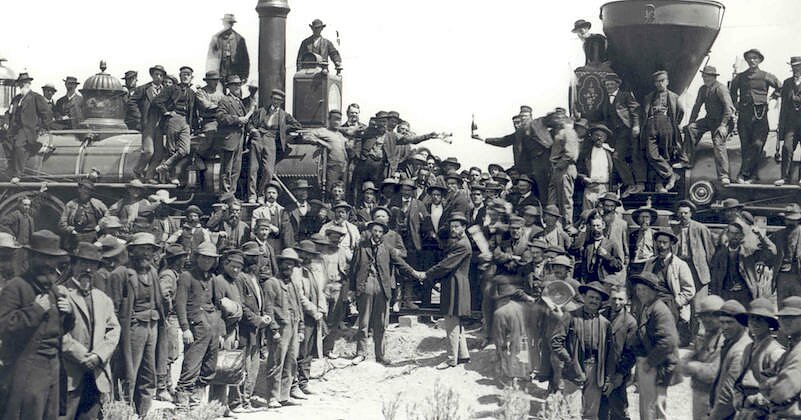

In 2014, Takaki followed Lee to Promontory, Utah, where the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed. Lee’s aim was to recreate the original 1869 commemorative photo which predominantly featured white representatives from the two railroad companies. For this version, however, Lee invited over one hundred Chinese Americans to the shoot to pay homage to the fact that without their labor, the grand project of the American West may have never been realized. It was an act of what Lee would come to refer to as “photographic justice.”

The film unfortunately offers only cursory mentions of such earlier, more radical involvements. Still, Takaki manages to capture a level of vulnerability, revealing a palpable ambivalence, perhaps just fear, in Lee’s later years about what was to become of his legacy and archive. He hoped to put together a book (Working title “Not on the Menu”) but found little interest outside of ethnic studies departments and the academic press. If he couldn’t find a buyer, he resolved to self-publish. (A posthumous catalog, Corky Lee’s Asian America, was released April 9 by Penguin Random House.) Laid off from his longtime day job at a printing press for ethnic periodicals, which allowed him the flexibility and financial backing to pursue photography, at one point Lee admits to counting down the months until his Social Security eligibility.

As Chinatown reckoned with a series of concurrent crises during the pandemic—the shuttering of businesses and an uptick in violence against its residents—Lee continued traversing its streets, camera in tow. He died shortly after in 2021 due to complications from COVID-19. The camera is alongside his loved ones at the funeral, watching the crowds of masked mourners pay homage to the late photographer. But this scene is just a blip toward the end, followed by some brief remarks on sacrifice. In the very spirit of Lee, it wouldn’t feel right to linger on tragedy when there’s so much else worthy of celebrating.

—Amanda Chen is a writer from California now based in Brooklyn. Her work has appeared in Catapult, the New Republic, Triangle House Review, and elsewhere.